MORE INFORMATION

Ventilator/Ventilator Support What Is a Ventilator?

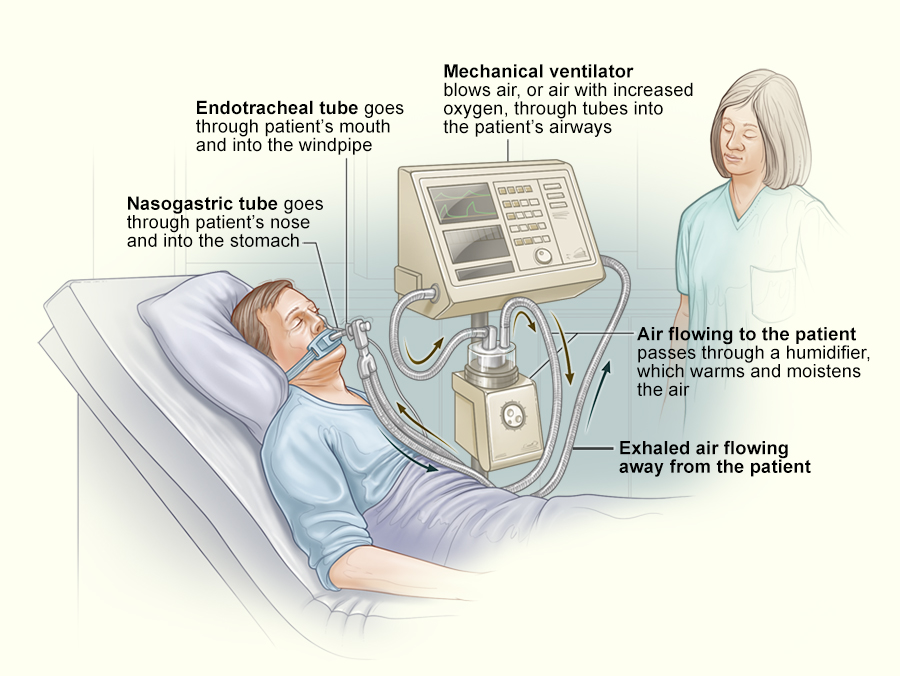

You may be put on a mechanical ventilator, also known as a breathing machine, if a condition makes it very difficult for you to breathe or get enough oxygen into your blood. This condition is called respiratory failure. Mechanical ventilators are machines that act as bellows to move air in and out of your lungs. Your respiratory therapist and doctor set the ventilator to control how often it pushes air into your lungs and how much air you get.

You may be fitted with a mask to get air from the ventilator into your lungs. Or you may need a breathing tube if your breathing problem is more serious. When you’re ready to be taken off the ventilator, your healthcare team will “wean” you or decrease the ventilator support until you can start breathing on your own.

Mechanical ventilators are mainly used in hospitals and in transport systems such as ambulances and MEDEVAC air transport etc. In some cases, they can be used at home, if the illness is long term and the caregivers at home receive training and have adequate nursing and other resources in the home. Being on a ventilator may make you more susceptible to pneumonia, damage to your vocal cords, or other risks or problems.